Welcome to the archaeology lab’s very first blog post! I’m beyond excited to step into my new role as the Society’s archaeologist this year, and let’s just say—I’m feeling charged up for the journey ahead. (Yep, that’s a little pun, because my amazing team of volunteers and I have been busy using electrolysis to conserve iron artifacts for Dr. Charles Cobb and Dr. Gifford Waters of the Florida Museum of Natural History).

The Backstory: Spanish Florida Missions

Before starting my position, I helped excavate a 17th-century Spanish Florida mission site just north of Gainesville, Florida. The site, San Francisco de Potano (1606–1706), was the longest-lived Spanish Catholic mission in the Florida interior.

Spanish Florida missions with a resident friar generally had five main components: a church, a friar’s residence, a detached kitchen, a plaza, and the surrounding Native American community. But mission San Francisco de Potano wasn’t just any Spanish Florida mission—it was the principal town of the Potano Timucua chiefdom. That means it likely had a chief’s house and a council house as well, making it not just a religious center but also a political hub for neighboring Potano Timucua communities.

Like buildings today, Spanish Florida mission structures combined a variety of nails, from small tacks to large spikes. During my fieldwork at San Francisco de Potano, I helped recover close to 200 wrought iron nails dating to the mission’s occupation—quite a nice haul! On top of that, our team uncovered a handful of artifacts I like to call “mystery metal” because, under all that rust, it’s anyone’s guess what they might be (for more background, check out FLMNH).

Why Conserve Iron?

Iron artifacts recovered from archaeological sites—especially in humid settings and marine environments—are often heavily corroded and unstable. Without proper treatment, they:

Did you know? While we were busy conserving artifacts from a Spanish mission site in Florida, let’s not forget that coastal Georgia had its own network of Spanish missions, too!

Right here on St. Simons Island, there were two—Santo Domingo de Asajo and San Buenaventura de Guadalquini. These missions were part of Spain’s larger effort to spread their influence (and faith) across the Southeast, connecting communities from Florida all the way up the Georgia coast.

- Continue to deteriorate after excavation, often visible as “weeping iron” or “rust blooms.”

- Pose contamination concerns of nearby artifacts, especially in shared storage.

- And can lead to increased conservation costs if left untreated, or irreversible loss.

What is Electrolysis?

Electrolysis is a conservation method that uses an electric current to remove corrosion products (primarily rust) from an artifact’s surface. It also extracts corrosive chloride ions, helping to prevent further deterioration.

How Does Electrolysis Work?

The iron artifact is submerged in an electrolyte solution (usually sodium carbonate in water). A low-voltage electric current is passed through the solution. The artifact (cathode) slowly sheds harmful chlorides, which are attracted to the anode, and corrosion layers. The process is monitored closely to record its progress, and overall:

- Help preserve artifact details while halting decay.

- Stabilizes the artifact for final sealing treatment, allowing for long-term storage, study, and display.

What Steps for Electrolysis are Taken at Our Lab

Step 1: Setup and Submersion

A metal fixture is placed over top of a tank and connected to a power source—in our lab, we use a 6V manual battery charger—to initiate the electrolysis process. Iron artifacts are suspended from this fixture in the solution. As the current flows, hydrogen bubbles begin to form around each artifact (a telltale sign of the reaction underway!), corrosion starts to loosen, and harmful chlorides are released and attracted to a steel plate (the anode).

Step 2: Monitor and Maintain

Regular monitoring is essential. We inspect artifacts daily, watching for signs that corrosion is beginning to peel away. During this stage, gentle manual cleaning is introduced to remove loosened corrosion. Patience is critical since deeply embedded rust may require weeks of electrolytic submersion to be fully clean for stabilization.

Step 3: Boil and Dry

Once electrolysis is complete, the artifact is immersed in boiling water to neutralize any remaining contaminants. We do a total of four boils, each of which lasts at least four hours. Between boils, artifacts are inspected for any residual oxidation—if any is found, we grab our tools and go to work! After boiling, artifacts are thoroughly dried and examined. Like before, if any residual oxidation is detected, we grab our tools!

Step 4: Seal and Protect

Finally, artifacts are immersed in hot microcrystalline wax for at least two hours, which penetrates and seals the surface of the artifact. This protective layer prevents further oxidation, leaving the artifact stabilized and ready for permanent storage, exhibition, and research.

And just like that, history preserved one rusty artifact at a time! And as a bonus, the wax coating can be removed—in conservation lingo, that means it’s reversible!

Charging Forward!

None of this valuable conservation work would be possible without the dedication of volunteers such as Myrna Crook and Janis Rodriguez. Before I joined CGHS, Myrna and Janis had conserved hundreds of iron artifacts from the Gorgia coast, including a cannon ball housed and curated at Fort Frederica National Monument.

The wrought nails and “mystery metal” conserved in our tanks may not be as explosive as a cannon ball. Yet, they’re an important part of history as they help tell—or in this case, frame, like a structure held together by nails—stories about the past.

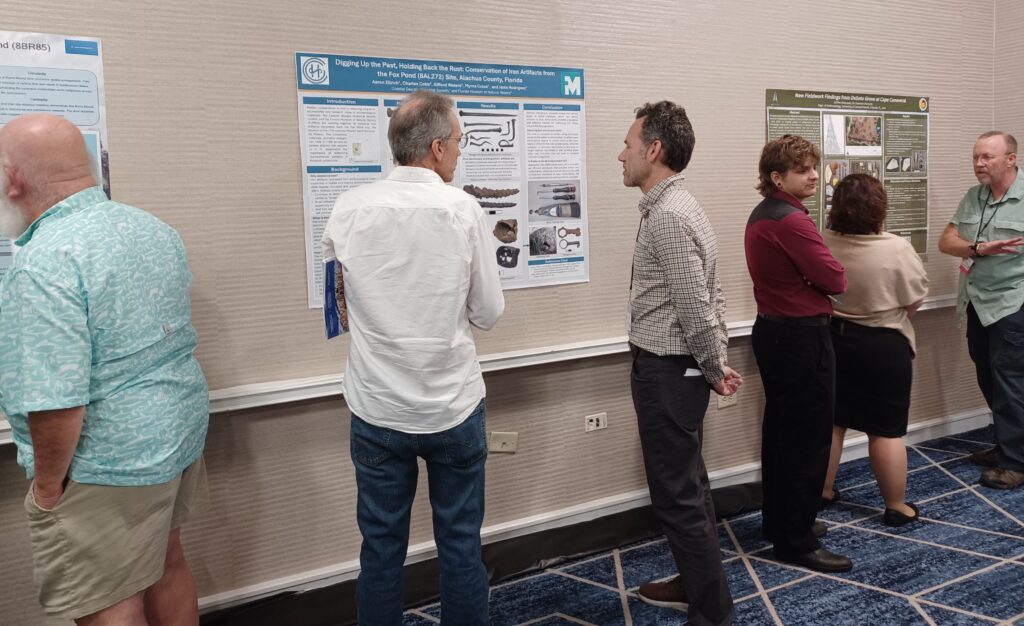

And speaking of stories, this month I had the chance to share our work at the 77th Annual Meeting of the Florida Anthropological Society in Gainesville, Florida. The poster, titled “Digging Up the Past, Holding Back the Rust: Conservation of Iron Artifacts from the Fox Pond (8AL272) Site, Alachua County, Florida” was a great opportunity to highlight our team’s work in preserving these important artifacts.

Until next time!